Taste-altering fruit: the miracle berry

Drinking vinegar that tastes like lemonade, and other misadventures.

My throat burned as I gulped down five mouthfuls of vinegar, and yet there was a sweet sensation on my tongue. No, this isn’t the start to some fancy metaphor for life or a poetic description of any obstacles I’m facing. There was an acidic burning sensation in my throat while my tongue was telling my brain that each drop of that vinegar was strawberry-sweet.

What’s happening here? This seems factually incorrect. However, through some accident of nature, we have a berry, that after we consume it, makes sour things taste sweet (and as I found out, made each bite of the strawberry taste like summer).

There are two things here that are equally fascinating:

What’s going on here chemically?

How did this berry come into existence?

Also... why do I let my friends fool me into doing the craziest things? Drinking vinegar was not as delicious as they promised me it would be.

1: Chemistry!

What type of compound makes sour things taste sweet to us? A glycoprotein known as miraculin is responsible. It binds to taste receptors on our tongue, causing acidic substances to register as sweet.

A glycoprotein is characterized by having a carbohydrate group attached to its polypeptide chain.

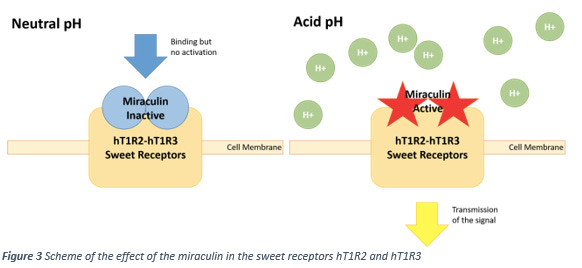

Here’s a pretty good visualization - let’s go through the mechanism in detail.

In normal conditions (when we don’t have any glycoproteins changing the way we normally perceive taste), when we consume something sugary, the molecules can bind to the sweet receptors (hT1R2–hT1R3), activating a coupled receptor, which then sets off a chain of events within the membrane, cell, and cell pathways, causing us to perceive the food as sweet.1 Interesting fact: there are two sweet receptors: one is optimized for smaller molecules, and the other for larger molecules.2

Miraculin changes that. When we consume the miracle berry, miraculin forms a very thin layer over our tongue (and stays there for just over an hour). It binds to our sweet receptors.3

When our mouth is at a neutral pH, our taste buds function as normal. However, at an acidic pH - such as when we consume the citric acid in lemons or acetic acid in vinegar and pineapples - the higher presence of H+ causes the carbohydrate section of the miraculin to bind to the sweet receptors, causing the same effect as if we had consumed something sweet.4

Interestingly, even when the miraculin is inactive, it suppresses the response of our sweet receptors to other sweet things at a neutral pH, and enhances it at a weakly acidic pH.5 That must be why the strawberries I ate tasted like liquified sugar - strawberries by nature have citric acid.

This really goes to show you how much of our experiences depend on our own bodies and minds… and got me thinking about if my perception of sweetness is the same as someone else’s.

The miracle berry and the miraculin it has can be helpful for cancer patients who are going through chemotherapy.6 Some of them develop taste distortion (dysgeusia) that prevents them from enjoying food the way they normally can. Skimming through this article, I found stories as to how cancer patients reported that miracle berries helped restore their taste back to normal!

2: Why does it exist?

We don’t know. There’s no reason for there to be a plant that evolved solely to ensure that humans could suck on lemons and have them taste like sweet tangerines.7 But we do have some good theories as to what happened!

Evolution typically happens because of some reproductive advantage or feature that increases chances of surviving until the age where the organism can reproduce.

There was a study that looked into the genome of the miracle berry and its close relatives, and found that perhaps miraculin was beneficial to the plant itself: it is important for “regulating seed germination and maturation, resisting pathogen infection, resisting environmental pressure, and regulating plant growth”.8 The way it alters taste perception could be just a happy accident.

The miracle berry is also most likely insect-pollinated.9 Another theory suggests that the plant has an advantage for seed dispersion when insects consume the fruit (and its seeds by extension) as future acidic foods will taste sweet.

I wonder if there are any other taste-altering plants that have evolved naturally… Perhaps that’ll be a blog for next time.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1084952113000268

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5105965/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1084952113000268

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5105965/

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1016644108#sec-2

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/jco.2010.28.15_suppl.e19523

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.804662/full

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.804662/full

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/08/160829163520.htm